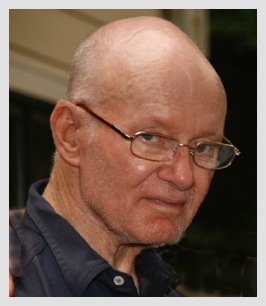

Francis Grover Darsey, Jr., “Frank” to almost everyone, was born in Lynn Haven, Florida, in the Florida panhandle north of Panama City. He was born on January 18, 1935 and died on October 13, 2013 at the Gilmer County Nursing Home in Ellijay, GA, the community in which he and his second wife, Helen, spent their last independent years together.

A memorial service was held in Ellijay at the Bernhardt Funeral Home on October 25, attended by Frank’s three oldest children and two of his grandchildren; his first wife (my mother), Sharon; his older sister, Sarah, and her husband, my Uncle Arch. Dad’s cousin Pat Ham was there as was my cousin Joe and his wife Carmen. There were a few of Frank’s friends and a couple of friends of the family.

Frank and his second wife, Helen, had arranged to be “inurned” (a new word I’ve learned from the funeral folks, “inurned” and “cremains”) in Manasota Memorial Park down where Dad spent most of his growing up years, including high school and where Dad and Helen met over 60 years ago. I represented the immediate family in Sarasota, and the service there was attended by Dad’s brother Leonard and Leonard’s wife Judy; their daughter Karen and their son David; and Karen’s two boys, Dad’s great nephews, Alex and Daniel. My cousin (Dad’s niece) Sheila was there with her daughter Kathleen. One of Helen’s daughters, Shannon, was there as were several of Dad’s friends from high school.

Dad’s death ended, not only his journey, but also a journey my brother Dale and I took with him and with each other in the two-plus years since Helen died. In that time, we had to take Dad’s driver’s license away; we had to move him from one assisted-living facility to another; and from regular assisted-living to the “memory community” (lock-down for patients with dementia, especially those prone to wander); and from memory community to “skilled nursing.” I remember the day we had to say to him, “Dad, you don’t get better with Parkinson’s.” Over months, we steadily consolidated his personal belongings to fit in smaller and smaller spaces; each time we had to do this, we understood that we were diminishing his life. We (Dale mostly) managed his assets, trying to ensure that he would have means so that we could make meaningful choices for as long as possible. His decline was startlingly precipitous. Just over two years ago, he was still driving the roughly 90-minute trip from Tucker to Ellijay. In his last year, he went from walking on his own, to using a walker, to a wheelchair, to a c-chair. It was shocking, especially in the last eight months, to see him so frail and so infirm.

Just a year ago, almost exactly, Dale and I took a day to tour facilities in north Georgia and into North Carolina. It was only a matter of time before Dad required more care than an assisted-living facility in Georgia is licensed or equipped to provide. On that day, just a year ago, we agreed that Dad wasn’t ready for a nursing home; he didn’t look like the people in a nursing home, people who were just being warehoused while they waited to die, the most exciting moment of the day lining up in their wheelchairs to rush the dining room at meal time, those who were able. When in September we finally did move him to the nursing home in Ellijay, Dad was indistinguishable from the other residents.

It was an emotionally fraught journey. Dale and I spent hours together, and we talked about what we were feeling. Every visit with Dad was an invitation to look to see what we could find in the shrinking shell of the man who had been our father, and there were always glimmers. Every visit, as we projected our genetic material twenty, twenty-five years into the future begged the question Scrooge asks of the Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come “

Are these the shadows of the things that will be, or are they shadows of things that may be, only?”

I was surprised at the humor and good grace with which Dad suffered his last two years. Of Elizabeth Kübler-Ross’s now classic five stages of dying, denial was the one I saw most in evidence. This is not to say that Dad was always easy to work with. Often he was not, driving even my good natured brother, at one point, to declare himself through with the affair. And staff at Benton House reported that he could sometimes be aggressive and uncooperative. But the general sense was that people liked Frank. That was important to him. If there was anger at his end, I didn’t see that, nor bargaining. I’m not certain that, for Dad, there was anyone to bargain with, and it is to his credit that, as the end approached, he did not retreat to some convenient deity created in a desperate moment. As Voltaire is reported to have said on his deathbed as he was being urged by friends to renounce Satan, embrace God, and take last rites: “This is no time to be making new enemies.”

The last conversation I had with Dad was marked with his characteristic humor. I had just moved him to the Gilmer County Nursing Home, and as I was leaving, after the intake interview, I stopped by to see how he was doing. He had been almost comatose on the trip up. But now, he was awake, and the Gilmer County nurses were doing their initial assessment. His last couple of months at Benton House, we had been required to have a 24/7 companion sitter--liability issues; Dad was a fall risk--at a cost of about $10,000/month. Dad was running through limited resources quickly. This was one of the factors that determined the timing of the move to Gilmer County. To the very end, Dad was attuned, in his own way, to issues involving money, and when Dale and I explained to him that his continued stay at Benton House required the companion sitter and how quickly he would exhaust his resources and have no choices for the next stage of care, he seemed to understand and to endorse the move to Gilmer County. When I stopped in his room to say good-bye that day, his first question was “What are you doing up here?’ His second question was “How much is this costing?” Dale and I always said that when we stopped joking with Dad, he would know that the game was up, so I replied “More than you’re worth at this point.” To which he responded, “Well, looks like I’ll have to get a job.”

James: “Yeah, we’re gonna set you up working a street corner, plying your wares.”

Frank: “I’m gonna have to rip off an arm and beat you with it.”

James: “If you can do that, there are a lot of zombie films being made in the area. I think I can get you a part as an extra.”

Frank: “Har, har, har.”

Those were the last words we ever exchanged. Subsequent visits, he was not fully awake or aware. Some have occasion to look back and regret the last exchange between themselves and a deceased loved one. I do not. I think this last exchange was, in many ways, the perfect way to have said good-bye. It avoided a sentimentalism that Dad would have found embarrassing; it left much unspoken but understood. I don’t know if it indicated that Dad had fully achieved Kübler-Ross’s last stage, acceptance, but he had, at least, reached a point of accommodation.

I suspect it’s always the case that the death of a parent is complicated. It was with great relief that I returned to Sarasota-Bradenton to see Dad’s ashes placed in a mausoleum wall at Manasota Memorial Park. The warm breeze, the sunny sky, the palm trees, the slight whiff of salt water, the natural fecundity of the area all seemed rejuvenating, the antithesis of the decay that Parkinson’s had wrought. Small wonder Ponce de Leon is said to have searched for the fountain of youth in Florida; the vitality of the area is overwhelming, even today as it is overrun with development.

As I said in my eulogy (which is attached

here, a amalgamation of remarks made in Ellijay and remarks made at Manasota with some additional editing--in the finest tradition of 19th-century speakers--for “publication”), I don’t know what Dad believed about or hoped for regarding an afterlife. I do know that we have taken him home, and that is all we on this earth can do.

There is also a

small album of photos from the Manasota service. Unfortunately, everyone was too preoccupied to remember to take photos at the service in Ellijay. To view the Manasota slides as a slide show, click on the first photo, then use the navigation arrows at the top of the screen to scroll through.